Each morning up and down the Maine coast, thousands of lobster boats head out for a day of hauling and then return to sell their catch to wharfs and buying stations. The fact that virtually all of Maine’s lobster fishing fleet – some 5,500 strong – is comprised of day boats sets it apart from many other fishing fleets which head out for days or weeks at a time (think of the big fishing fleets in New Bedford and Gloucester, MA). Most of us, when we think of the iconic lobster boats steaming out of our harbors, do not think about the behind-the-scene intricacies. As a board member of the Tenants Harbor Fisherman’s Co-op, which I played a small role in helping set up, I felt I had a reasonable understanding of how lobster-fishing industry operated. But as I learned when I jumped in to help at the wharf when we were short on workers, the logistical intricacies behind a lobster getting from the ocean floor to your plate are not for the faint of heart.

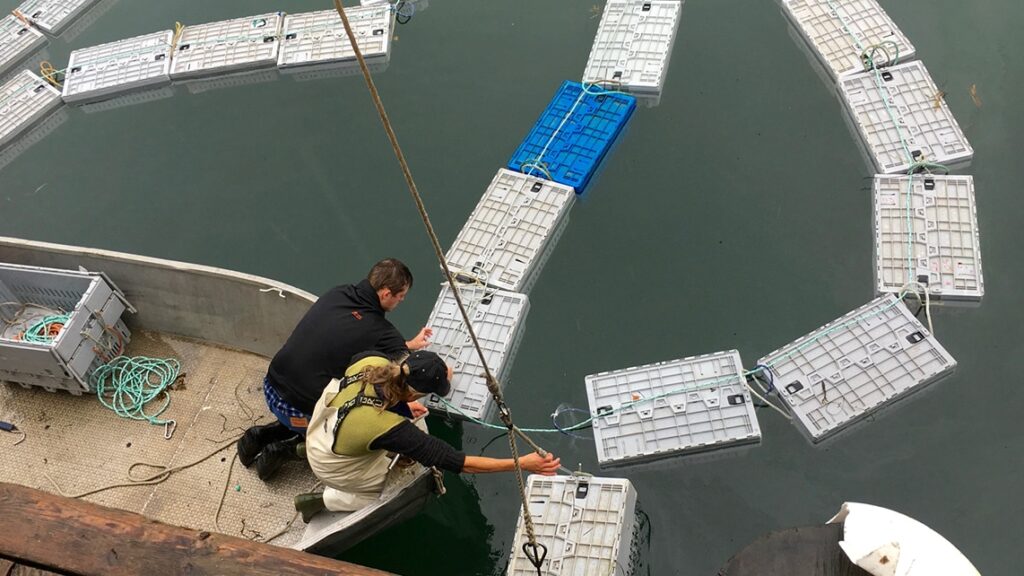

The first task I was charged with was helping take lobsters out. It was a cool rainy Sunday, the wharf had only a few boats out hauling and our wharf manager had a well deserved day off. When I arrived, the truck was already there waiting, and Josh, a kid who helped out at the wharf, had gone out in the wharf skiff to tow the crates in. Our co-op ships its lobsters on a near-daily basis during the busy season. The day I helped we were shipping 120+ crates. We keep the crates stored at our buy float out towards the middle of the harbor where the water is cooler and has better circulation, towing them into the wharf just before they are shipped. Once Josh brought the crates in, I scrambled down the ladder and jumped on the skiff. Up above, one of our co-op members worked the hydraulic hoist, lifting each 90-lb crate out of the water and loading it on a pallet. James, the co-owner of the trucking company Oceanland, then loaded them onto a truck to take our lobsters to Cape Seafood, for processing before their final destination at Luke’s Lobsters.

As a general matter, I get anxious when people watch me work, especially when I’m trying to figure out how to do something new. The task at hand was simple by any standard: hook each crate to the hydraulic lift so it could be hoisted up, get the next crate ready, repeat, 120+ times. But with the most experienced guys running the hoist above me and the rain making the aluminum skiff slippery, I felt slow, inefficient in my work. The coaching from above – “Merritt, use the gaff to line them up and run that string of crates to the stern – tie it off to the cleat there,” – generally served to confuse rather than help me. By about the 100th crate, I was starting to get the hang of it.

While working I thought how this process was emblematic of the industry as a whole – individual fishermen in a closed fishery hauling traps one by one, measuring every lobster, banding each lobster, off loading them one by one into 90lb crates, and now, taking the crates out one by one. There was nothing about the industry, despite its incredible landings, that allowed for commercialization or scale, protecting both a way of life and the fishery itself.

Once the crates were finished I thought I was done for the day, but when I took the skiff back out to the buy float to return a few partial crates mistakenly brought in, one of our boats was steaming in – its lobsters would need to be offloaded, weighed and bought. Having been hauling quite a few times, I knew how the process worked, or at least I thought I did.

When one of our boats comes in, the first stop is the buy float, which can accommodate two boats, one on either side. It’s equipped with a scale and all the necessary administrative tools to buy lobsters: slips, calculator, pens, etc., a floating office of sorts.

The process is the same for every boat that comes in. The boat ties up to the buy float, takes crates aboard and sternmen begin emptying lobsters from the holding tanks into the crates. The lobsters are sorted as they are offloaded: new shells in one crate, hard shells in another and “selects” in a third – they all have different (and constantly changing) prices. The sternmen load each crate almost full – the idea is to get the crate as close to the 90lb standard as possible. Once the crate is loaded, it’s carried over to the scale – mostly the crates are a little on the heavy side, and lobsters are taken out and put into a “partial” until the crate weighs 90lbs exactly. Each 90lb crate is closed, labeled with the fisherman’s name and put at the edge of the buy float. All of this I did seamlessly, but with the weighing complete, I realized I had to actually write the slip up and though I’d seen it done dozens of times, I realized I had no idea what the mechanics of it were.

“I think you’re going to need to help me write the slip,” I said to Peter whose lobsters I had just crated.

“Okay, name, date, on this line, where it says new shell, number of crates x 90; and then the partial; the next line same thing for hard shell and then same thing for select. Okay so for new shell 4 x 90 plus my partial of 44lbs, and put the total weight here, so 4 x 90 plus 43, what’s that?” I am not a numbers person and definitely not a form person: all this rattled off to me in staccato gave me the familiar sensation of being called on in class to do something you should really know how to do, but find yourself at a complete loss. “403lbs,” he answered his own question, more than likely noting the deer-in-the-headlights expression on my face. “Okay now we do the same for hard-shell and selects.” I fumbled my way through the buying part of the slip – several cross outs later. “Okay, for bait, I had 4 trays of herring, and red heads, you put that on this line here, and the price is written right here on the board.”

I handed him his slip, it was one of a triplicate – yellow for the fisherman, pink for wharf records and white for our bookkeeper. I bought lobsters from several more boats that day, each time the process became a little more intuitive. When the boats were all in I brought the wharf skiff back into the dock and tied it up. As I headed home, I passed by the bait shed and realized for all the day’s learning, I had only scratched the surface: Monday marked the start of the week, the day I knew most fishermen would bait up. Tomorrow would be bait.